Islamic writers in the Middle Ages and early modern period (ninth to nineteenth centuries) practiced a number of prose genres—history, biography, and travelogue among them—but poetry in the Persian language was considered the highest form of literary accomplishment. Persian was the language of high culture in the Islamic world, and many royal courts used Persian as their official language. Poetry was associated with venerable Arabian oral traditions as well as the poetic quality of the Qur'an, and mastery of this genre in Persian or Arabic required extensive knowledge of languages and texts. Poets were important members of royal courts, holding much higher positions than painters, for example. In the relationship between art and literature in the Islamic world, the word always took precedence over the image. Only in the modern period do visual artists achieve the same level of fame and fortune as their literary counterparts.

In Islamic manuscripts, images serve mainly to illustrate the texts provided, which does not mean that the images were not enjoyed as artistic creations themselves or that the work of painters was completely derivative. This situation simply indicates the working conditions painters faced in the Islamic world. As an adornment to the excellence of Persian poetry, Persian painting achieved great fame in the visual arts. And like poetry, Persian painting was exported across Islamic lands, with famous poets and painters collaborating to create luxurious, lavishly illustrated literary manuscripts.

Miniature: Line Drawing of Artist at Work, ca. 1600, Persian, 62.205

Related Objects in SAM's Collection

Photo: Paul Macapia

Farhad carving Shirin's portrait, probably 18th century, Persian, 40.37

Photo: Paul Macapia

Khosrow Discovers Shirin at her Bath, mid-16th century, Northern Iranian, Shiraz School, 50.69

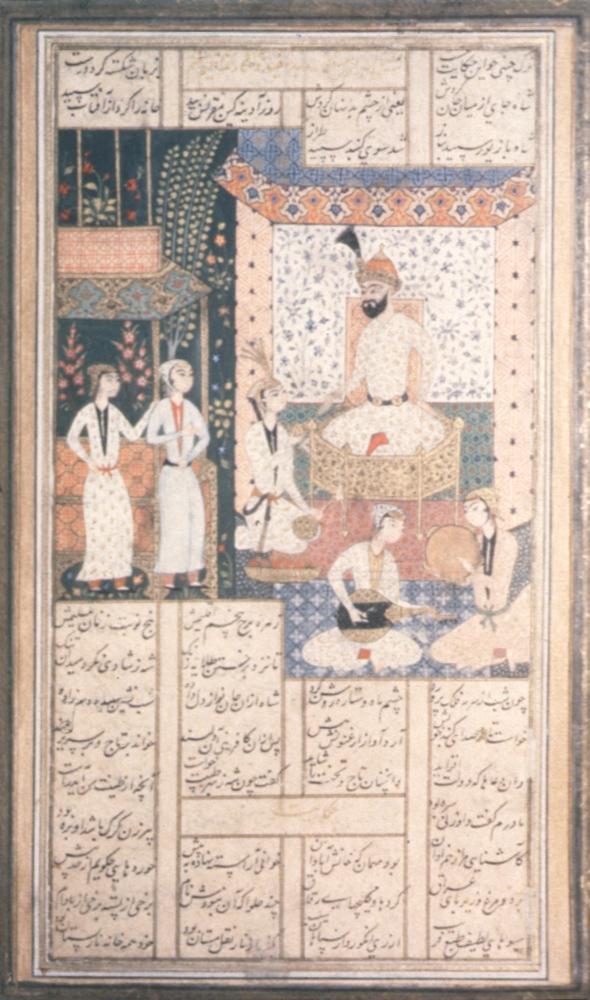

Princess from Turkestan before Bahram, 16th century, Persian, 47.16

Poetry was the highest form of literary achievement in medieval and early modern Persia, and the fame of Persian poets spread throughout the Islamic world. Authors such as Nizami, Jami, Sa'di, Hafiz and Rumi generally composed poetic works in rhyming couplets, or masnavis, and published them in anthologies or collections of texts. One of the most beloved of these anthologies was the Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami. Although the Shahnama (Book of Kings) was considered the greatest work of epic Persian poetry, the Khamsa was the most popular example of Persian love poetry. The variety of illustrations of Nizami's stories point to the enduring popularity of the Khamsa in the Islamic world.

Indeed, the stories in the Khamsa lend themselves to illustration. They combine didactic works (Makhzan al-Asrar, or Treasury of Secrets, and the Haft Paykar, or Seven Portraits), love stories (Layla and Majnun, Khusrau and Shirin) and heroic tales (Iskandarnama), several of which feature subjects from the Shahnama as their protagonists. Nizami's greatest originality resides in his complicated and tragic love stories, where love is to be understood on literal, physical, metaphorical and spiritual levels.

Khosrow Discovers Shirin at her Bath, mid 16th Century, Northern Iranian, Shiraz School, 50.69