Resources

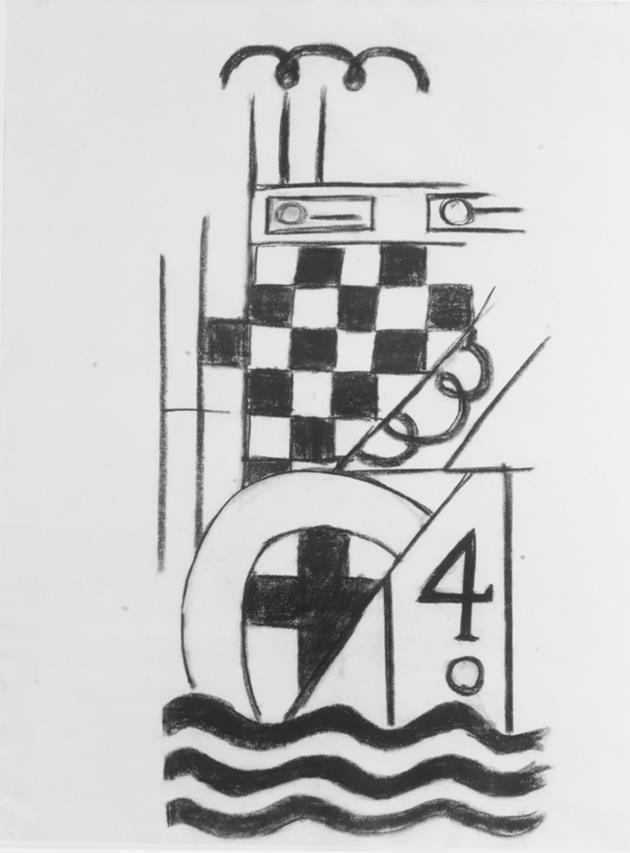

Exhibition History{Berlin, Germany, Münchener Graphik-Verlag. [Forty-five paintings and a group of drawings, executed in Europe after Oct. 1912], Oct. 1915.}

New York, New York, The Little Galleries of the Photo Secession, 291, Exhibition of Paintings by Marsden Hartley, Apr. 4 - May 22, 1916.

Albion, Michigan, Albion College, Marsden Hartley: A Retrospective Exhibition Lent by Hudson D. Walker of New York, Apr. 15 - 30, 1950. Checklist no. 6.

New York, New York, Martha Jackson Gallery, Marsden Hartley: The Berlin Period 1913-1915: Abstract Oils and Drawings, Jan. 3 - 29, 1955. Checklist no. 5.

Lincoln, Nebraska, University of Nebraska Art Galleries, 1957 - 1958 [extended loan].

Ogunquit, Maine, Museum of Art of Ogunquit, Sixth Annual Exhibition, June 28 - Sept.8, 1958. Cat. no. 22.

Chicago, Illinois Institute of Technology, The Maremont Collection at the Institute of Design, Apr. 5 - 30, 1961. Cat. no. 38, reproduced.

Washington, D.C., Washington Gallery of Modern Art, Treasures of Twentieth Century Art from the Maremont Collection at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, Apr. 2 - May 3, 1964. Cat. no. 47, reproduced.

Phoenix, Arizona, Phoenix Art Museum, Classics of Contemporary Art from the Maremont Collection, 1968. Cat. no. 14, reproduced.

Edinburgh, Scotland, Royal Scottish Academy, under the auspices of the Arts Council of Great Britain, The Modern Spirit: American Paintings 1908-1935, Aug. 20 - Sept. 11, 1977 (London, England, Hayward Art Gallery, Sept. 28 - Nov. 20, 1977). Cat. no. 40, reproduced p. 10.

Düsseldorf, Germany, Städtische Kunsthalle, 2 Jahrzehnte amerikanische Malerei 1920-1940, June 8 - Aug. 5, 1979 (Zurich, Switzerland, Kunsthaus Zurich, Aug. 23 - Oct. 21,1979; Brussels, Belgium, Palais de Beaux-Arts, Nov. 15 - Dec. 31, 1979). Cat. no. 26, pp. 60, 62, reproduced p. 26.

New York, New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, Marsden Hartley, Mar. 4 - May 25, 1980 (Chicago, Illinois, Art Institute of Chicago, June 10 - Aug. 3; Fort Worth, Texas, Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, Sept. 5 - Oct. 26; Berkeley, California, University Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley, Nov. 12, 1980 - Jan. 4, 1981). Text by Barbara Haskell. Cat. no. 30, pp. 44, 215, reproduced pl. 81, p. 156.

Saint Louis, Missouri, Saint Louis Museum of Art, The Ebsworth Collection: American Modernism, 1911-1947, Nov. 20, 1987 - Jan. 3, 1988 (Honolulu, Hawaii, Honolulu Academy of Arts, Feb. 3, 1988 - Mar. 15, 1988; Boston, Massachusetts, Museum of Fine Arts. Apr. 6 - June 5, 1988). Text by Charles E. Buckley, William C. Agee, and John R. Lane. Cat. no. 31, pp. 13, 18-20, 33,106-107, 207-208, reproduced p. 107.

National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., American Impressions: Masterworks from American Art Forum Collections, 1875–1935, March 27–July 5, 1993, as Painting No. 49, Berlin, lent by Mr. and Mrs. Barney A. Ebsworth.

Seattle, Washington, Seattle Art Museum, In the American Grain, February 8 – May 5, 1996 (organized by Philips Collection, traveled also to Museum of Modern Art, Saitama, Japan; Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art, Japan; Chiba Municipal Museum of Art, Japan; Portland Art Museum).

Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, Twentieth Century American Art: The Ebsworth Collection, Mar. 5 - June 11, 2000 (Seattle, Washington, Seattle Art Museum, Aug. 10 - Nov. 12, 2000). Text by Bruce Robertson, et al. Cat. no. 27, pp.16, 126-127, 285, reproduced pp. 6 (detail) and 127.

Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, Modern Art and America: Alfred Stieglitz and his New York Galleries, Jan. 28 - Apr. 22, 2001. Text by Sarah Greenough, et al. No cat. no., pp. 235, 532, reproduced pl. 72, p. 234.

Hartford, Connecticut, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Marsden Hartley, Jan. 17 - Apr. 20, 2003 (Washington, D.C., The Phillips Collection, June 7 - Sept.7, 2003; Kansas City, Missouri, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Oct. 11 - Jan.11, 2004). Text by Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, et al. Cat. no. 21, pp. 296-297, reproduced p. 91.

Seattle, Washington, Seattle Art Museum, SAM at 75: Building a Collection for Seattle, May 5 - Sept. 9, 2007. No catalogue.

Los Angeles, California, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Marsden Hartley: The German Paintings, 1913-1915, Aug. 3 - Nov. 30, 2014.* Text by Dieter Scholz et al. No cat. no., p. 124, listed p. 204, reproduced p. 87. [*organized by Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, but shown In Los Angeles only.]

Seattle, Washington, Seattle Art Museum, From New York to Seattle: Case Studies in American Abstraction and Realism, Jan. 15, 2020 - June 5, 2022 [on view Jan. 15, 2020 - Mar. 13, 2022].

Seattle, Washington, Seattle Art Museum, American Art: The Stories We Carry, Oct. 20, 2022 - ongoing.

Published ReferencesG. Alan Chidsey, Trustee for the Hartley Estate. Volume of Photographs of Paintings, Pastels, Drawings and Lithographs by Marsden Hartley Washington, D.C 1944–1960. Archives of American Art, G. Alan Chidsey Papers, #142, as Painting No. 49, Berlin.

McCausland, Elizabeth. Elizabeth McCausland Papers, 1838-1995, bulk 1920-1960 Series 6: Marsden Hartley, 1900-1964 (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.), 14.4.19–20 datasheets, as Painting No. 49, Berlin. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/elizabeth-mccausland-papers-7839/subseries-6-2/box-14-folder-4.

Getlein, Frank. "Art and Artists: A Wide Variety in Maremont Show," The [Washington, D.C.] Sunday Star, April 5, 1964, C5, reproduced.

Levin, Gail. "Hidden Symbolism in Marsden Hartley's Military Pictures," Arts Magazine 54, no. 2 (October 1979): pp. 154, 156-157, reproduced fig. 2 [as Berlin Abstraction].

cf. Barry, Roxanna. "The Age of Blood and Iron." Arts Magazine 54, no. 2 (October 1979): p. 171.

Robinson, William H. "Marsden Hartley's Military," The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 76, no. 1 (January 1989): pp. 12-15, reproduced.

McDonnell, Patricia. Dictated by Life: Marsden Hartley's German Paintings and Robert Indiana's Hartley Elegies. Exh. cat. Minneapolis: Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum, 1995; reproduced p. 47.

Cikovsky, Nicolai, Jr. "Peter Blume". Twentieth-Century American Art: The Ebsworth Collection. Exh. cat. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1999; p. 49.

Weiss, Jeffrey. "Marsden Hartley". Twentieth-Century American Art: The Ebsworth Collection. Exh. cat. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1999; pp. 126–29.

Robertson, Bruce. "The Ebsworth Collection: Histories of American Modern Art". Twentieth-Century American Art: The Ebsworth Collection. Exh. cat. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1999; pp. 16, 27.

Corn, Wanda M. "Marsden Hartley's Native Amerika". Marsden Hartley, edited by Elizabeth M. Kornhauser. Exh. cat. New Haven and London: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2002; p. 81.

Robertson, Bruce. "Marsden Hartley and Self-Portraiture". In Marsden Hartley, edited by Elizabeth M. Kornhauser. Exh. cat. New Haven and London: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2002; p. 153.

Ellis, Amy, Elizabeth M. Kornhauser, Townsend Ludington, and Kristina Wilson. "Catalogue Entries". In Marsden Hartley, edited by Elizabeth M. Kornhauser. Exh. cat. New Haven and London: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2002; p. 309.

Updike, John. Still Looking: Essays on American Art. New York: Alfred Knopf, 2005. Monograph, discussed, p. 150, as Painting No. 49, Berlin.

Ngo, Dung., ed., with essay by Franklin Kelly. Art + Architecture: The Ebsworth Collection + Residence. San Francisco: William Stout Publishers, 2006; n.p., reproduced.

Ishikawa, Chiyo. "SAM at 75: Building a Collection for Seattle," SAMconnects 21, no. 2 (Spring 2007): p. 13, reproduced p. 12.

Unsigned. "Seattle Art Museum to Mark 75th Year With May 5 Event". Antiques and The Arts Weekly (Newton, CT), April 27, 2007: p. 55, ill.

Junker, Patricia. "New York Stories." In A Community of Collectors: 75th Anniversary Gifts to the Seattle Art Museum. Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 2008; p. 203, reproduced p. 202, pl. 170.

Junker, Patricia. "A Sense of Place." The Magazine Antiques 174, no. 5 (November 2008): p. 115, reproduced p. 90.

Property from a distinguished European Collection. Christie's New York. Important American Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, lot 16. Christie's. New York: Christie's, May 21, 2008; pp. 35-36, fig. 12.

Junker, Patricia. "Childe Hassam, Marsden Hartley, and the Spirit of 1916." American Art 24, no. 3 (Fall 2010): pp. 41-47, reproduced p. 42, fig. 12, and cover.

Messinger, Lisa M. Stieglitz and His Artists: Matisse to O'Keeffe. The Alfred Stieglitz Collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011; p. 135.