Potlatch is term of Chinook jargon that means "to give." It refers to a complex ceremony that is important throughout Northwest Coast and involves sharing wealth and maintaining the social and political position of leaders. Some of the reasons to stage a potlatch include raising house posts or totem poles, naming children, passing down family dances and songs, marriages and memorials. Guests are invited to witness the proceedings and receive gifts as payment for their services as witnesses. Witnessing is crucial to the event because it serves to confirm that the family hosting the potlatch does indeed have the right to the dances, songs, masks and other treasures that are displayed during the potlatch. New masks are carved, regalia made, and the skills of many artists, singers, composers and dancers are engaged.

The host family, with the valued assistance of many relatives, assembles the food for feasting and the goods to be given as gifts. In times before contact with westerners, gifts might include food, carved boxes and bowls, headdresses, jewelry, basketry and weavings. After contact, gift-giving sometimes reached elaborate levels and could involve cash, bags of flour, boxes of pilot bread, enamel and glass kitchen wares, sewing machines, furniture, piles of Hudson's Bay Company wool blankets and even diesel-powered boats. In the modern era, gifts include cash and Pendleton-type blankets for special guests, food, fruit, dishes, towels, scarves and sometimes hand-crocheted items and silkscreen prints. A large potlatch can cost many thousands of dollars and, in the old days, last from several days to several weeks.

During the nineteenth century, potlatching was discouraged by missionaries who deemed it a heathen practice, by Indian agents who wanted to assimilate Natives and be certain that children were in school, and by employers who needed a reliable work force. The Canadian government passed legislation in 1885 that banned the potlatch, a restriction that was not lifted until 1951.

A display of articles to be given away at a potlatch, Alert Bay, BC, early 20th century, William May Halliday

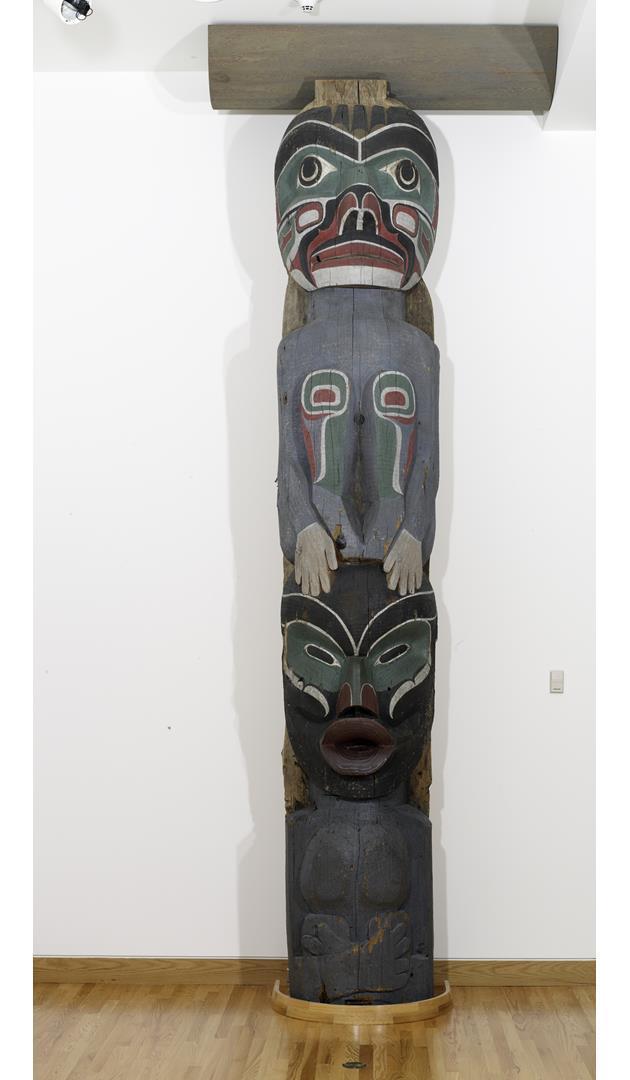

British Columbia Archives, H-03976Crests are hereditary family emblems that represent supernatural entities or mythic ancestors whose deeds and powers established the histories of the families. The representation of clan and family crests on ceremonial regalia (such as masks) and monumental sculpture (such as house posts) is fundamental to Northwest Coast Native culture. The display of crests demonstrates one's history, wealth and rank and links living people to their ancestors. Crests can be transferred through marriage and, in former times, were acquired in warfare.

The kolus, a type of supernatural thunderbird seen prominently on these posts, is said to have descended in myth time from his celestial home in human form and to have married a descendant of the Scow family. That is why the family can claim the kolus as a crest.

Detail of thunderbird, 82.169.1

The Story of the House Posts Before They Came to SAM

House posts at the Pacific Science Center, 82.169.1-2

House posts at the Pacific Science Center, 82.168.1-2

House posts at the Pacific Science Center, 82.168.1-2

Codfish Mask, ca. 1970-71, Sam Johnson, SC2006.1

Bakwus Mask, ca. 1970-71, Sam Johnson, SC2006.2

Porcupine Mask, ca. 1970-71, Sam Johnson, SC2006.3

Kingfisher Mask, 1970-71, Sam Johnson, SC2006.4

Grizzly Bear Mask, ca. 1970-71, Sam Johnson, SC2006.6

Deer Mask, ca. 1970-71, Sam Johnson, SC2006.7

Mouse Woman Mask, ca. 1970-71, Sam Johnson, SC2006.8

Raccoon Mask, ca. 1970-71, Sam Johnson, SC2006.9

Wolf Mask, ca. 1970-71, Sam Johnson, SC2006.10

If We Don't Potlatch, Our Hearts Will Break

The public display of a family's privileges-songs, stories, and dances-is a necessary demonstration of social status and inheritance of those privileges generation to generation. In the words of one elder, "The potlatch is our court of law and it is where we transact important business," like giving names to our children, transacting marriages, installing new leaders and passing down family treasures. (George Bennett)