Masks were important accessories for dance dramas that included elaborate regalia (costumes) and the names, songs and dances associated with the creature or individual being depicted. It is possible that shamans were the first to use these masks, which were then adopted for social ceremonial uses some time later. The use of masks by shamans in the early historic period (the late eighteenth century) is well established, especially for the Tlingit, and to a lesser extent the Tsimshian and Haida, but these traditions probably predate this period. The use of masks is probably ancient, yet there is little archaeological data to support this thesis. The evidence suggests that shamanic practices were well established 2500-3500 years ago, probably earlier. The small pendants, figures, and stone bowls bearing images of skeletalized humans, animals and composite beings that have been found in archaeological sites have similarities to shamanic items from later times. In some Northwest Coast cultures, shaman's had masks with images of ancestors or humanoid supernatural beings.

Masks are all in some way a means by which the presence of supernatural beings and their powers were made tangible. We can classify masks into two broad categories: those used for crest display during ceremonial re-enactments of mythic events, when the wearer might be imbued with the power of the creature the mask represents, and those worn by shamans and ritualists during curing rites or during initiations into secret societies. These distinctions are not hard and fast, and there were, no doubt, social and spiritual aspects to both categories of masks.

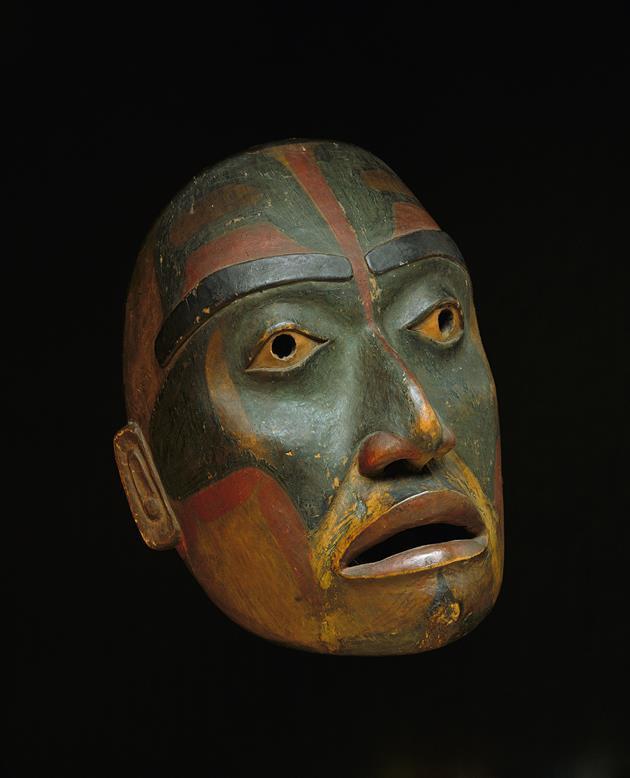

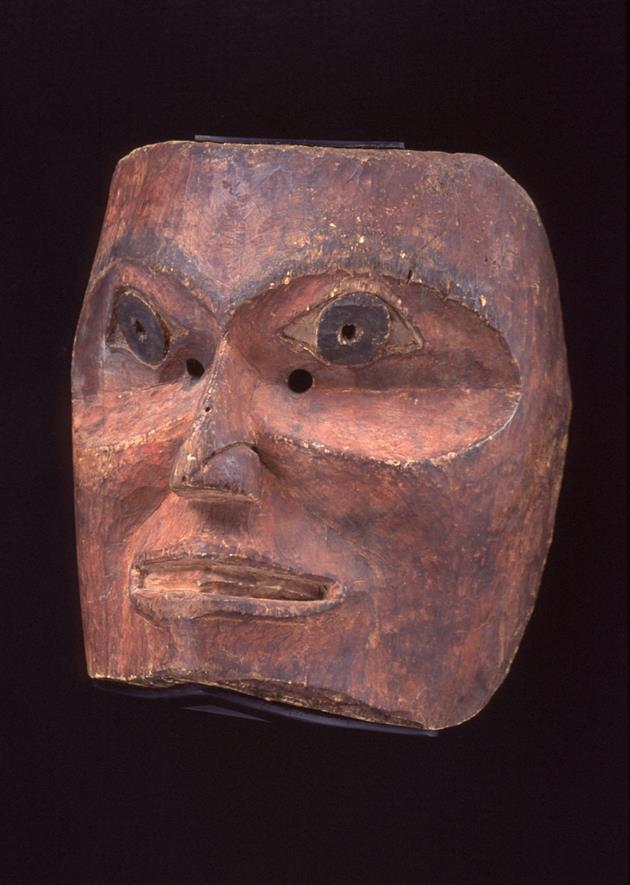

Niijaang.u (portrait mask), ca. 1840, Haida, 91.1.38

Most of us associate Northwest Coast native masks with dramatic animal and supernatural creatures. It might come as a surprise to learn that some masks were made as portraits of individuals, such as ancestors, shamans, warriors and chiefs. Because the story dramatized by the mask is integral to knowing who the mask represents, we often don't know who is being depicted because the story is not collected with the piece.

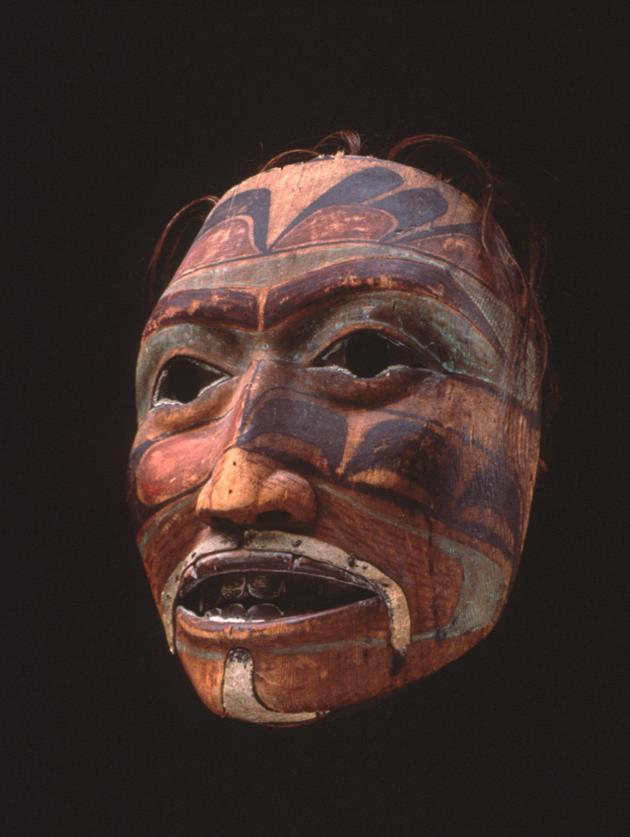

Is this Mask Tsimshian or Haisla?

© Canadian Museum of Civilization, VII-C-329, Photo: Harry Foster, S89-1820

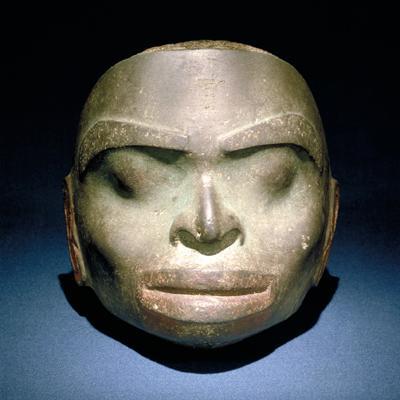

Mask, n.d., Tsimshian, stone, 9 7/16 x 8 7/8 x 7 1/8 in.

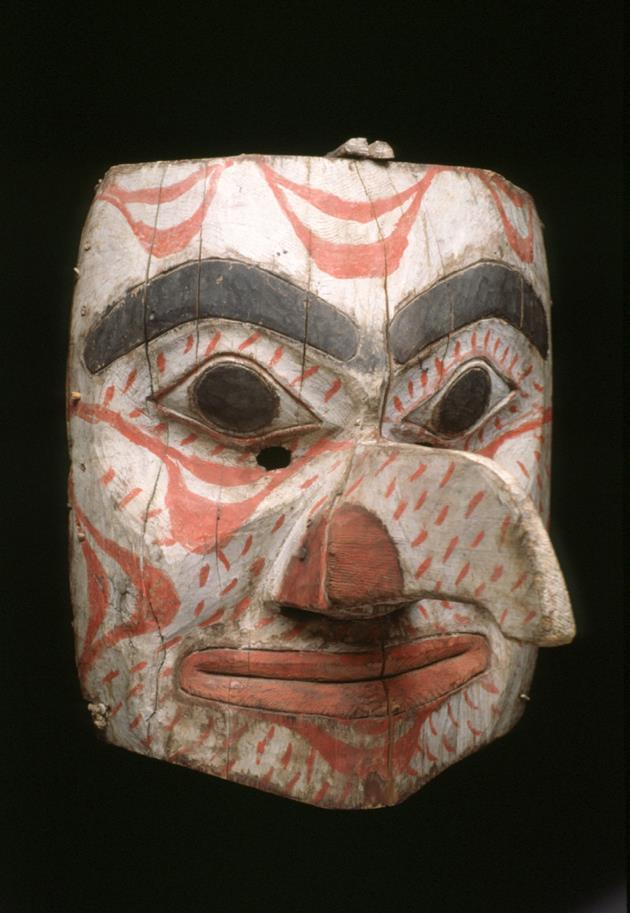

Large Face Mask, representing "Giant", ca. 1900, Tsimshian, 91.1.49

Large Face Mask, ca. 1890, Tsimshian, 91.1.48

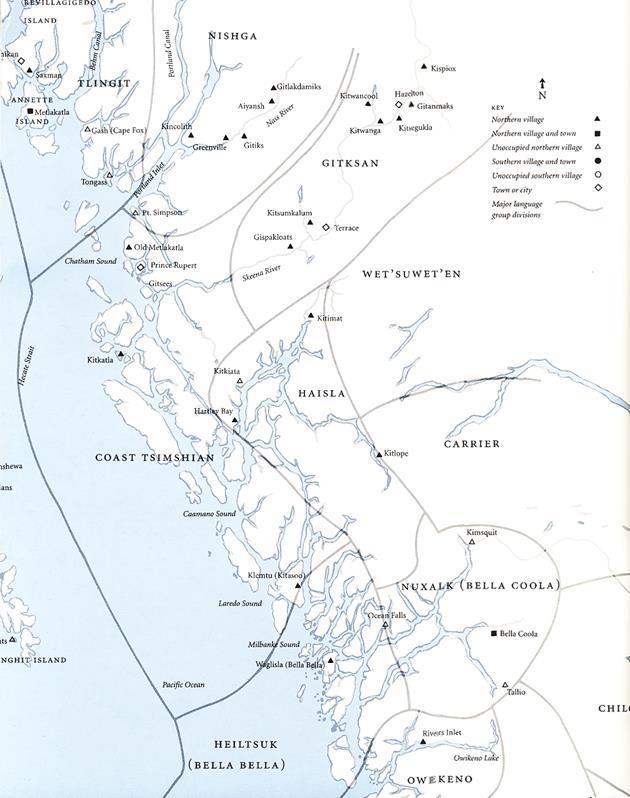

The Haisla are the Wakashan-speaking linguistic neighbors of the Kwakwaka'wakw of mainland British Columbia, as are the Heiltsuk, Haisla, Oweekeno and Haihais. Each of these subdivisions was composed in historic times of several independent villages. Living in the upper reaches of Douglas Channel and Gardner Canal on the northern, inner coast of British Columbia, Haisla villages were isolated until about 1850, when deaths from epidemics caused the survivors to consolidate to the Heiltsuk town of Bella Bella and the Haisla town of Kitimaat, near the southern boundary of the Coast Tsimshian people. Haisla people had cultural and trade relations with the Nuxalk and the Tsimshian. The Tsimshian are composed of three groups: the Coastal group whose territory includes the modern city of Prince Rupert, the Nisga'a of the Nass River, and Gitxsan of the upper reaches of the Skeena River, some two hundred miles from the coast. Tsimshian artists used the northern formline design system, as did the Haisla, but in distinctive ways. There appears to have been artistic similarities between the two groups, which is especially obvious in the making of portrait masks.

Map of the Northwest Coast

© Seattle Art Museum