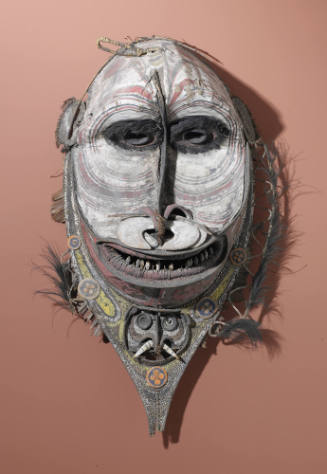

Gelede Mask: Male with Skull Cap

Dateearly 20th century

Maker

Southwestern Yoruba

Maker

Nigerian

Maker

Amosa Akapo

Maker

Igbe Quarter

Maker

Igbesa

Label TextA Muslim cleric is commemorated in this headdress whose mouth seems about to speak or chant. To complete the impression of a devout Muslim, a performer wearing this mask might carry prayer beads, a prayer mat, and a teapot used to wash his face and feet before reciting verses from the Koran. The key to this man's identity is suggested by the amulets on his cap. In former centuries, Muslim clerics in Yoruba courts supplied protective amulets to leaders and holy persons.

Christians and Muslims participate in Gelede, and Muslim support for Gelede has remained constant, despite disapproval of other masquerade forms. In turn, Gelede is circumspect in its criticism-Islam, a religion that sixty percent of all Nigerians now follow, would not become a target. Instead Gelede focuses attention on certain kinds of individuals whose eccentricities invite satire.

The word Gelede describes a spectacle that relaxes and pacifies the beholder. Gelede is primarily dedicated to the maternal principal in nature personified as Iya Nla, the Great Mother; it is also aimed at promoting peace and social harmony within a particular community.

The first part takes place at night, the Efe ceremony. During the ceremony, a mask called Efe-which means the humorist or joker-performs throughout the night, praying to the Great Mother to be very generous to the society. At the same time, the mask criticizes anti-social elements in the society. The emphasis of the Efe mask is on satire, on poetry.

At dawn, the Efe will withdraw, and then the crowd will gradually disperse. In the afternoon of the second day, small children come out to perform their own Gelede. By five o'clock, the marketplace is filled up once more, and then other Gelede masks arrive from different sections of town. Daylight masks do not sing-whatever they want to say is in the headdresses.

Other masks depict important leaders in the community, including priests of many origins. This particular headdress wears a Muslim hat adorned by triangular packets which normally conceal Koranic verses. Gelede publicly acknowledges the roles of these priests in the spiritual uplifting of the community: it is to encourage all members of a given society to interact as if they were children of the same mother.

As a result of the transatlantic slave trade between the sixteenth and late nineteenth centuries, hundreds of thousands of Yoruba were transplanted to the New World. Many of them took Gelede with them, and Gelede performance continued into the early twentieth century. Around 1988, a society known as the Society of Yemaya was formed in New York. In Gelede, nature becomes the nurturing element of culture with the Great Mother. Yemaya is personified as the Great Mother who could provide for people during slavery, and continued to do so in Cuba and Brazil. Gelede ceremony also influenced the carnivals of the Caribbean, and Mardi Gras in New Orleans. Yorubas were present in large numbers in New Orleans. There is a Yoruba village in Sheldon, South Carolina where there is a shrine dedicated to Yemaya, there are paintings and sculptures illustrating Gelede and Yemaya-so the Gelede tradition has been transformed in various ways in the Americas.

Gelede headdresses were collected as far back as the 1880s, if not earlier. Some European missionaries asked their converts to surrender their masks. There are representations of Gelede masks in the works of European artists dating back to the nineteenth century. But most of the collectors did not bother about the names of the artists, they simply yanked off the headdress because that was regarded as most important. Retired headdresses were often given to children to practice with, but these days, they may be sold to dealers.

Object number81.17.585

Provenance[Merton D. Simpson Gallery, New York]; purchased from gallery by Katherine White (1929-1980), Seattle, Washington, 1964; bequeathed to Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, Washington, 1981

Photo CreditPhoto: Paul Macapia

Exhibition HistoryLos Angeles, California, Frederick S. Wight Art Gallery, University of California, African Art in Motion: Icon and Act, Jan. 20 - Mar. 17, 1974 (Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, May 5 - Sept. 22, 1974). Text by Robert Farris Thompson. No cat. no., pp. 202-3, reproduced pl. 246 (as "Gelede" mask).

New York, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Master Hand: Individuality and Creativity Among Yoruba Sculptors, Sept. 12, 1977 - July 1, 1978.

Seattle, Washington, Seattle Art Museum, Praise Poems: The Katherine White Collection, July 29 - Sept. 29, 1984 (Washington, D.C., National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, Oct. 31, 1984 - Feb. 25, 1985; Raleigh, North Carolina Museum of Art, Apr. 6 - May 19, 1985; Fort Worth, Texas, Kimbell Art Museum, Sept. 7 - Nov. 25, 1985; Kansas City, Missouri, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Mar. 8 - Apr. 20, 1986). Text by Pamela McClusky. Cat. no. 35, pp. 78-79, reproduced (as Gelede mask).

Seattle, Washington, Seattle Art Museum, Art from Africa: Long Steps Never Broke a Back, Feb. 7 - May 19, 2002 (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Oct. 2, 2004 - Jan. 2, 2005; Hartford, Connecticut, Wadsworth Atheneum, Feb. 12 - June 19, 2005; Cincinnati, Ohio, Cincinnati Art Museum, Oct. 8, 2005 - Jan. 1, 2006; Nashville, Tennessee, Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Jan. 27 - Apr. 30, 2006 [as African Art, African Voices: Long Steps Never Broke a Back]). Text by Pamela McClusky. No cat. no., pp. 12, 227, 238-39, reproduced pl. 95.Published ReferencesBrodd, Jeffrey, World Religions: A Voyage of Discovery, pg. 26Credit LineGift of Katherine White and the Boeing Company

Dimensions7 15/16 x 8 x 12 in. (20.2 x 20.3 x 30.5 cm)

MediumWood, pigment, and leather

log in

log in