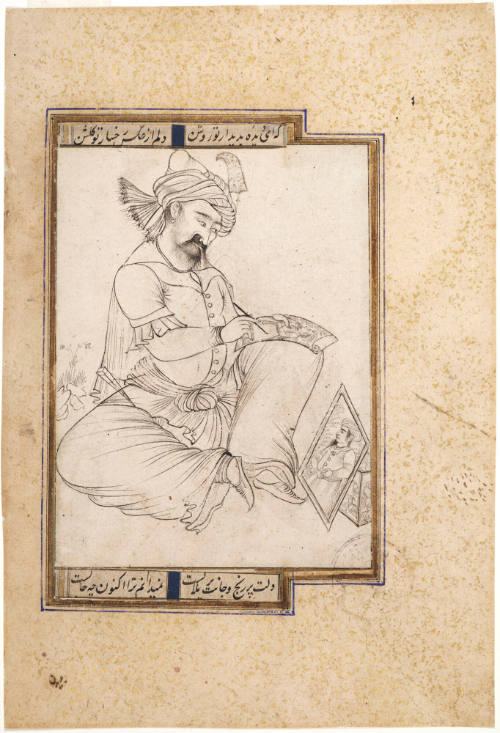

Calligraphy; An artist at work

Dateca. 1600

MakerIranian (

Persian

)

Label TextFrom the 15th century onward, Persian rulers and courtiers had their artists create muraqqa’ (albums) made up of collected or specially created calligraphy and images. This page shows calligraphic fragments in the flowing nastaliq script favored by Persian calligraphers. The fragments are from the romance of Yusuf (Joseph) and Zulaikha, wife of King Potiphar, as retold in the Haft Awrang (Seven Thrones), a compilation of stories and anecdotes composed in the late 15th century by the Persian poet Jamī.

The subject of the image does not relate to the written romance. Instead, it shows a painter copying a portrait of a male courtier that is propped in front of him. The tapering black brush lines echo the flow and rhythm of the calligraphy. Such monochrome paintings are called siah-qalam (black pen) and were originally inspired by Chinese monochrome brush paintings imported to Iran during the rule of the Mongol Il-Khanid Dynasty (1256–1355).

Some Islamic manuscripts feature members of the court at work. A royal court was filled with a variety of people, including soldiers, scribes, doctors, magicians, entertainers, artists, cooks and pages. Artists such as the one depicted here in great detail played important roles in court life. Through their work, artists entertained and amused the ruler and his entourage and demonstrated the ruler's worldliness and sophistication as a supporter of the arts. The importance of painters, particularly those who created illustrations for books, can be seen in the large number of illuminations that exist to this day.

In this image, we see an artist at work in a landscape setting. The artist copies the work of another master, with the original propped up before him. Copying works by others was not considered derivative or unimaginative in the Islamic world. Aspiring painters were required to perfectly copy the works of known masters before they were allowed to branch out and develop their own styles.

In this image, we see an artist at work in a landscape setting. The artist copies the work of another master, with the original propped up before him. Copying works by others was not considered derivative or unimaginative in the Islamic world. Aspiring painters were required to perfectly copy the works of known masters before they were allowed to branch out and develop their own styles.

Object number62.205

ProvenancePurchased from A. Vecht, Amsterdam, July 5, 1952

Photo CreditPhoto: Paul Macapia

Exhibition HistorySeattle, Washington, Seattle Asian Art Museum, Boundless: Stories of Asian Art, Feb. 8, 2020 - ongoing [on view Feb. 8, 2020 - July 11, 2021].Credit LineEugene Fuller Memorial Collection

Dimensions6 9/16 x 4 1/2 in. (16.6 x 11.4 cm)

MediumInk, gold, and watercolor on paper

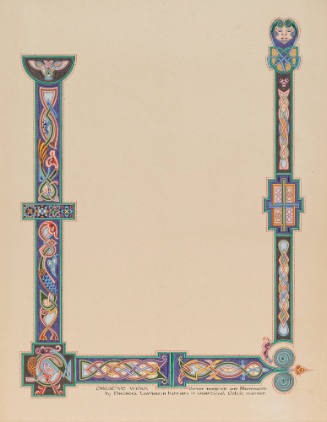

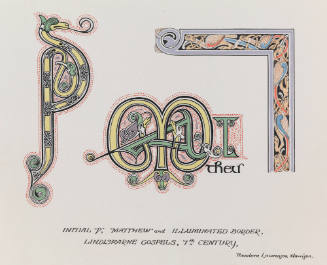

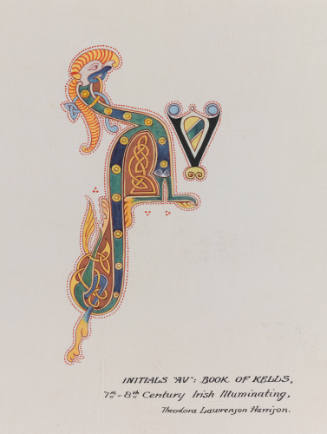

Theodora Harrison

1934 or 1935

Object number: 2013.6.1

Theodora Harrison

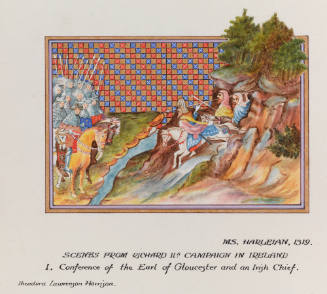

1934 or 1935

Object number: 2013.6.4

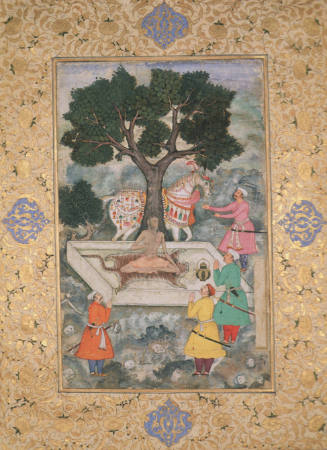

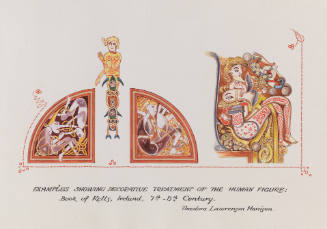

Theodora Harrison

1934 or 1935

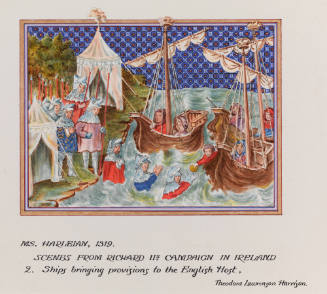

Object number: 2013.6.6

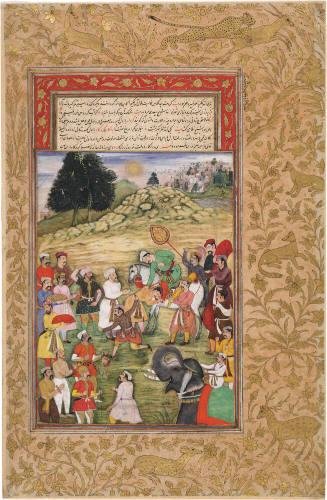

Theodora Harrison

1934 or 1935

Object number: 2013.6.7

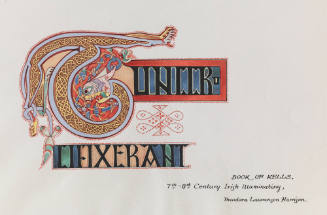

Theodora Harrison

1934 or 1935

Object number: 2013.6.8

Theodora Harrison

1934 or 1935

Object number: 2013.6.9

Theodora Harrison

1934 or 1935

Object number: 2013.6.11

log in

log in