Hollis Sigler

Hollis Sigler

Hollis Sigler was an accomplished artist with a career spanning thirty years. Sigler is best known for her faux-naif paintings and drawings that chronicle her battle with breast cancer. Her pieces express her fear, anger, and hope throughout the journey and have inspired other women to fight for their lives. Throughout her career Sigler lived mainly in the Midwest and used painting as an outlet for her dreams, memories, and emotions.

Hollis Sigler was born in Gary Indiana in 1948 to parents Phillip Sigler and Marilyn Ryan Sigler. The older of two children, Sigler’s artistic calling was clear from an early age. Philip Sigler was an engineer and was somewhat distant from the family, while Marilyn Ryan Sigler was a grade school teacher and had a close relationship with her children. The family moved briefly to Wisconsin before settling permanently in Cranbury, New Jersey, but Sigler always felt a strong connection to Indiana and her desire to return inspired many of her early artworks. She attended Moore College of Art in Philadelphia and spent her junior year abroad in Florence. Sigler experimented with an abstract expressionist style in her painting but by the time she graduated in 1970 she painted almost exclusively in a photorealist style. She continued painting in this style during graduate school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where her subjects mainly included underwater swimmers. Sigler graduated in 1973 with a Master’s Degree in Fine Arts. In September of that same year she collaborated with a group of artists to found one of the first women artists’ cooperatives in the Midwest, Artemisia Gallery. The gallery brought in prominent speakers and was a site for discussion on feminist art theory in which many women expressed their desire to break away from the “male paradigm.”

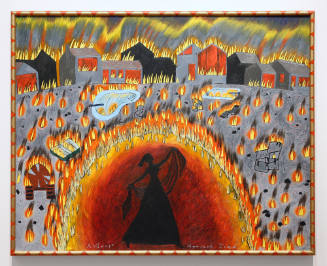

In 1976 Sigler had a breakthrough in her work, ignited by either a personal crisis, an attempt to disengage from a “male-dominated academic tradition,” or a combination of the two. Sigler abandoned photorealism, stating that she felt “a disconnect between myself and my work in an emotional sense.” She began painting in a faux-naif style, disregarding perspective and proportion. “Not knowing what to do with intense feelings of victimization I put down my paintbrush and began drawing without restraint, like a child,” she said. Gradually she worked her way back to painting, continuing to use the same, new visual language. The style, which she used almost exclusively for the rest of her life, employed vivid colors, skewed perspectives, and frequently included scrawled titles across the top or on the sides. In the 1980s Sigler explored themes of filial longing, romantic disaster, fear, anger, inadequacy, and victimization by lovers, parents, and herself. In order to avoid making “a spectacle of herself or the female body” or attracting the “male gaze,” figures appear very infrequently, and when they do appear they take the form of a silhouette that Sigler calls “The Lady,” her alter-ego. She drew inspiration from memories or dreams, and the scenes often took place in suburbia or in an empty interior space where the objects are left to tell the emotional narrative. Occasionally the environments are scenes of catastrophic fires, such as in A Tango Against Time (84.142), a part of the permanent collection at the Seattle Art Museum.

Although many artists in Chicago were experimenting with the fusion of “story-telling and naïve expressionism” at the time, Sigler’s work rose above many of her peers and she received praise from critics, who called her pieces “disturbingly successful.” She received overwhelming support from the feminist community and the Chicago art world, which helped launch her successful career and create a high demand for her artworks around the country. Her works were featured in the Whitney Biennial in 1981 and the Corcoran Biennial of 1985, and she had multiple other solo shows.

In 1985 Sigler was diagnosed with breast cancer, a disease which both her grandmother and mother had. Within six months she had a mastectomy and underwent radiation treatment. Sigler changed her lifestyle, became a vegetarian and practiced daily meditation in which she visualized the body’s immune system attacking the cancer cells. She continued to paint and write, but in her paintings she did not explicitly discuss the cancer or the causes for her emotions.

Sigler’s cancer recurred in 1989 and again in 1992, when she found out that it had metastasized to her bones. During this time she briefly experimented with a return to photorealism in her paintings, using waterfalls as her subject. The waterfalls were intended as a metaphor for the human body, although Sigler struggled with the seductiveness of the image and the danger of inviting the male gaze. She soon returned to her faux-naif style of drawing and painting, but this time she dealt directly with the subject of breast cancer. She decided to “go public” in an attempt to raise awareness about breast cancer and also spread a message of hope.

"When people hear the word cancer, they just go deaf. They don't hear that people live with this. Yes, we have to find a cure. First we have to find the cause. But, with treatment, people live; breast cancer doesn't mean you're going to die next week or next year," she said.

In 1992 Sigler began working on her most famous series, “The Breast Cancer Journal,” which was published in 1999, four years after she lost both her mother and her grandmother to the disease. She produced the series in collaboration with a doctor and an art historian as a book, The Breast Cancer Journal: Walking with the Ghost of My Grandmother. The series includes collage, oil paintings and pastel drawings, monotypes, and lithographs. Sigler often incorporated medical facts, statistics, and personal journal entries on the sides of the pieces, chronicling her physical and emotional battle with the disease.

Sigler exhibited her work in various shows and galleries across the United States including the following: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington D.C.; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; the Steven Scott Gallery, Baltimore; and the Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York. Her extensive, though truncated, career is represented in the permanent collections of museums such as the Seattle Art Museum, the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., The Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, and the Art Institute of Chicago. Throughout her career Sigler won multiple awards, including the National Endowment for the Arts grant for painting in 1987, an Honorary Doctorate from Moore College of Art in 1994, and a lifetime achievement award from the College Art Association one month before her death. She continued to paint almost every day until she passed away in 2001 after her long battle with cancer. Her autobiographical works gave strength, courage, and inspiration to keep fighting to countless other women battling breast cancer.

-Camille Coonrod, Curatorial Intern, 2014

log in

log in