Michael Spafford

Michael Spafford

Michael Spafford is a highly accomplished artist, with a career spanning over fifty years. Spafford was professionally trained as an art historian and as a painter, and his work is almost exclusively focused on Greek and Roman mythology. Although some of his works have sparked controversy in the Pacific Northwest and have divided the community over issues of government censorship of the arts, Spafford remains a celebrated artist who presents art-historical subject matter in a way that is relevant to today’s society.

Spafford was born in 1935 in Palm Springs to Sarah Alice Maloney. He was raised by his mother and his father, who he saw as distant. Spafford grew up in various small towns in the greater Los Angeles area as the second of three boys and battled health problems in his youth, including diabetes, which he cites as a major factor of his drive to create art. He attended Riverside High School, where he began to work for an advertising agency, creating lettering and ad layouts. Because of this, in the early phase of his life Stafford’s “take on art was more commercial,” he said. While in high school he took a Latin class for which he read Ovid’s “Metamorphoses” and then created an elaborate drawing of the mythological Roman underworld as an assignment – the origins of his interest in this recurring theme. He attended Riverside Junior College for two years and then enrolled at Pomona College in Claremont, California, where he studied art, philosophy, classics, and art history. In his first year he met art history Professor Peter Selz , who not only convinced him to stay at the school when he realized that his credits from Junior College would not transfer , but also introduced him to the work of Leon Golub when he arranged an exhibit of his sphinx series at Pomona in 1958. This exhibit exposed Spafford to contemporary works of art based on art-historical sources and figurative works that had the “visual impact of Abstract Expressionism.” He was also deeply inspired by Professor Teresa Fulton’s class on early Netherlandish art, which Spafford says influenced his “artistic sensibilities.”

While in his second year at Pomona, Spafford was involved in a near-fatal car accident that caused him to miss the end of a semester for recovery time. When he returned to Pomona the next semester, he found that “an attractive woman” had taken over his studio space. This woman, painter and sculptor Elizabeth Sandvig, would become his wife in 1959, the year they graduated. Spafford was an excellent student and was recognized on campus as a talented artist; Sandvig recalls that no one was better at drawing from the model than Spafford, not even the professors. Spafford graduated magna cum laude and was an Edward R. Bacon Art Scholar at Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences . He finished one academic year and was invited to return, but chose instead to move to Mexico with Sandvig, where they could live cheaply with Sandvig’s mother and paint full-time. It was here in Mexico City that Spafford discovered the works of Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siquieros, and José Clemente Orozco. He was drawn to the Mexican artists’ bold, often violent imagery paired with a “highly cultivated formal aesthetic.” Here in Mexico Spafford had a large space to work in and began to explore Greco-Roman mythology as a way to use his knowledge of art history in a socially relevant manner. It was during these three years that Spafford developed his characteristic process of working on one thematic series repeatedly for an extended period of time.

The couple moved to Seattle in 1963, the same year as the birth of their son, Michael Spafford (now Spike Mafford). Spafford began teaching at the University of Washington that same year as an assistant professor and soon began to receive positive reviews for his shows and awards for his works. In 1964 his “Origin myth No. 10” won first prize at the Pacific Northwest Arts and Crafts Fair, where it was reviewed by George B. Culler as “an extremely powerful painting presented with great force and direction.” Tom Robbins, Seattle Times art critic, added that Spafford was one of the only professors who had displayed “any originality and strength in the annual faculty show” that winter.

In 1965 Spafford exhibited 28 works in a one-man show at the Otto Seligman Gallery. Ann Faber, art critic for The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, wrote, “This is a strong, almost brutal show. The values, however, do not lie in shock but in a well-documented journey toward a new experience of the eye, linked to an old experience of the mind.” Later that same year Spafford received a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Grant in painting. He had his first exposure to controversy when one of his paintings was removed by Kemper Freeman, vice president of Bellevue Square Managers, Inc. from the Belleveue Arts and Crafts Fair in 1967 just three hours after the fair officially opened. The painting, titled “The Rape of Europa,” was seen as offensive by some viewers, but it was an embarrassment for the fair’s organizers as Freeman had acted without consulting the board, especially considering Spafford’s growing success.

In both 1967 and 1968 he was awarded a Prix de Rome Fellowship to study at the American Academy in Rome. For two years Spafford worked in a large studio space in Rome, and, because he was freed from the time constraints of being a full-time professor, he could dedicate all his time to painting. It was during this time that he fully realized the importance of painting for personal gain, rather than fame or commercial success:

But I did receive an awareness in Rome which induced work, which freed me to take greater chances and which convinced me of the ultimate value of “wasting” my life in pursuit of an occupation which might seem to some to be a pretty silly thing for a grown man to do.

Spafford also noted that he became much more aware of time, death, and the “tremendous sense of the heroic nature of the process of art in Rome, which manifests itself in magnificent attempts and magnificent failures.” This realization was to manifest itself throughout his following works.

Upon his return to Seattle, Spafford began to work on promoting public art. He founded The Artist’s Group (TAG) in 1971 and served as its president in 1974. The organization lobbied for the One Percent for Art Ordinances, which were adopted first by King County and the city of Seattle in 1973 and then by the state in 1974. Under the ordinance, 1% of the construction budget for public buildings is used to acquire and maintain public art. Spafford’s first public arts commission came in 1979, when he was selected by a jury, along with Jacob Lawrence, to create a large-scale mural at the Kingdome. The mural program was initiated by Val Laigo of the King County Arts Program. Spafford extolled the program and the creative freedom that it gave to artists. “This is an excellent program,” he said during the unveiling. “The county is the only agency which gives the artist carte blanche – no strings attached. As a result the public gets a chance to see what the artist can really do.” Spafford’s final piece, “Tumbling Figure—Five Stages,” was placed in a five story tall elevator shaft in the Kingdome and was composed of five black aluminum parallelograms with a male figure cut into the center of each. These segments were stacked vertically and show his characteristic style of bold human shapes with no modeling, providing a dynamic sense of movement for the viewer – a “violent sensation within a disinterested environment.”

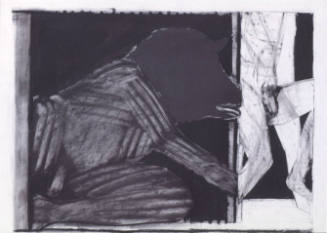

Vermillion Falling Figure (92.160), part of the permanent collection at the Seattle Art Museum, shows his continued experimentation with a falling form within vertically stacked parallelograms, although the artist said that this small painting, which was part of a series, was devoid of the mythological significance present in his other works. Spafford created this piece at a time when he was exploring the tripartite composition, which he first used as part of a set of formal exercises in which he depicted swimmers.

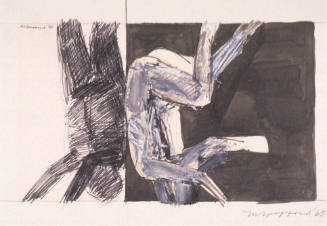

Shortly after the Kingdome mural was unveiled in 1980, Spafford won a commission to create a mural in the state House of Representatives in a highly selective competition, judged by a board of Washington citizens with varying interest in the arts, ranging from arts patrons to architects and educators. His plan was to create a four-part piece, with two parts depicting “The Labors of Hercules” and the other two depicting Icarus and a Chimera. The mural would show each of the Greek hero’s twelve “impossible” tasks as a metaphor for the legislative process. “The legislators wrestle with difficult problems, and so did Hercules. Sometimes Hercules did well and sometimes he did poorly,” Spafford explained. “My intent is to develop a visual activity. I don’t call them paintings. They deal with the verb side of what’s going on in politics. I am considering conflict, struggle, violence.” As part of the application process, Spafford recalled explicitly warning the jury that his work had been seen as controversial in the past. “I was very, very careful to tell the jury that a lot of people didn’t like my work. And they said they didn’t care.” The murals were executed in black and white, featuring extremely simplified human forms, which created a very flat, yet dynamic and pattern-like, and semi-abstract image.

Midway through progress on the murals, chaos broke out. A large number of legislators were highly displeased with “The Labors of Hercules,” and the conflict escalated quickly to a state-wide debate that raised issues of government censorship of the arts. House Speaker William Polk expressed his concern that the art clashed with the architecture, while many others described the artwork as “pornographic” and “obscene.” In a breach of contract, the Legislature cut off funding; this did not allow for Spafford to complete his proposed project and did not pay him for the last two murals. Soon after, a temporary wall was built to cover the works, and they remained covered until 1989, when they were uncovered for just four years before being put into storage, which cost nearly double what Spafford had been originally paid to create the pieces. The legal battle dragged on for years, and Spafford said he wished he had never created the pieces and would rather see them destroyed than moved to a different location.

Members of the arts community were quick to stand with Spafford, and he received institutional support from the Seattle Art Museum in the form of a solo exhibition, including The Twelve Labors of Hercules (82.1), now part of the permanent collection at the Seattle Art Museum. The show was given positive reviews by critics from the Seattle Times, Art Week, and Art in America. “The dialectics involved in his work… keep his continuing efforts from becoming stale,” wrote Ron Glowen, critic for Art Week. “In fact, his latest works offer a refined paint handling that is fresh and invigorating. The show is well-deserved recognition for an artist in his prime.” Spafford continued to receive support from the artistic community and was called upon to participate in multiple shows and received a commission for a piece at the Seattle Opera House in 1986. His later works utilize simplified forms and continue to explore Greco-Roman mythology, along with occasional swimmers and interpretations of poetry. His use of bold color and schematized form remains largely the same in the majority of his work, but he began to add fleshy tones to some of his pieces in some of his work in the 1990s.

Spafford has had solo and group shows throughout his career in galleries and museums across the United States and around the globe, especially in Seattle, Italy, and Mexico City. His work is represented in the permanent collections of the Seattle Art Museum, the Bellevue Art Museum, and the Mexican-North American Cultural Institute, Mexico City, among others. He has won multiple fellowships and awards, including the Visual Artist Award from the Flintridge Foundation in 2005/2006 and “Neddy” award in 1996, a $10,000 grant established in honor of arts patron Robert E. “Ned” Behnke. While his work has been some of the most controversial in the history of the Pacific Northwest region, it has gained national acclaim and through his paintings he connects the historical past with our current society in a way that speaks to the universal experience of humankind.

-Camille Coonrod, Curatorial Intern, 2014

log in

log in